How Zelda Keeps Mixing Fantasy with Sci‑Fi

A forty-year pattern, not a one-off switch

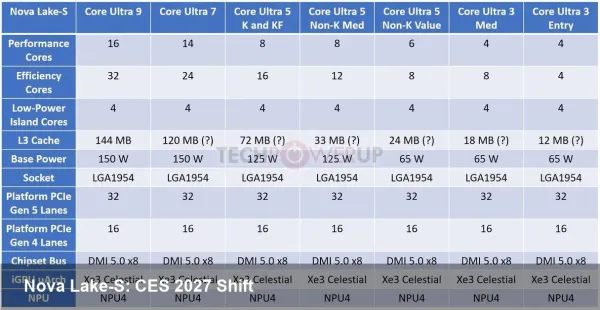

The Legend of Zelda turns 40 in 2026. Across that span Nintendo has repeatedly introduced elements that feel more like retro-futurism than medieval myth: falling moons, robotic guardians, energy barriers and flying islands. Rather than a wholesale genre shift, Nintendo tends to sprinkle science-fictional touches into a broadly mythic world, using them to surprise players, justify mechanics and deepen lore without abandoning swords and sorcery.

Why ancient technology works in a fantasy series

Using 'ancient tech' gives designers a convenient bridge between wonder and mechanic. A ruined automaton can explain a boss’s laser beams. A forgotten device can be the key that unlocks a traversal tool. That combination lets teams:

- introduce novel toys (glide modules, grappling rework, modular devices) without modernizing the entire setting;

- create environmental mysteries that players want to explore; and

- layer mechanics on top of narrative beats—shedding exposition through ruins, data logs or one-off scenes rather than heavy-handed dialogue.

Breath of the Wild (2017) and its follow-up Tears of the Kingdom (2023) exemplify this approach: Sheikah devices and Zonai components are both story elements and playground pieces that enable emergent player creativity.

Concrete design patterns inspired by Zelda

If you build games, these are transferable patterns:

- The relic-as-gateway: unlocks new traversal or combat options but is scarce, forcing choice-based progression.

- Modular toybox: a limited set of components that combine in player-driven ways (vehicles, traps, contraptions).

- Ruin-as-UI: visual cues in environmental design that teach interaction without explicit tutorials.

- Dissonant artifacts: a single, striking piece of tech inside a low-tech world that creates narrative tension and curiosity.

Example: give players three simple machine parts—motor, hull, and energy cell—and a physics sandbox. Players will iterate toward solutions you didn’t explicitly design for. That’s the same playful engineering Tears of the Kingdom encouraged with its placement and durability rules.

Developer workflow and technical constraints

Blending organic fantasy assets with mechanical sci‑fi raises practical issues:

- Art pipeline: teams need style guides and modular rigs so metal and stone read as part of a single world. Reuse base meshes and skins to reduce overhead.

- Physics & emergent systems: sandbox mechanics increase QA surface area. Build automated tests for edge-case interactions and invest time in deterministic simulation for multiplayer or replayability.

- VFX and audio: energy weapons and hovering devices demand distinct shaders and sound vocabularies. A consistent particle and SFX library helps maintain cohesion.

- Scripting & data-driven design: provide designers with low-code tools to tweak parameters (durability, energy, attachment points) without a full-engine merge.

For indie teams, the recommendation is to scope early: implement one modular mechanic and iterate until it feels expressive rather than adding multiple systems at once.

Business upside (and the risks)

A science-fantasy blend widens audience appeal. Players who want the comfort of swords and the novelty of gadgets both find hooks. This opens merchandising, cross-media storytelling and novel DLC ideas (e.g., device packs, community map challenges). Breath of the Wild’s success showed how a reinvented formula can reach new mainstream players while driving long-tail sales.

Risk management: core fans sometimes resist apparent genre drift. Preserve the series’ identity by anchoring new tech in established lore and by keeping core gameplay (exploration, puzzles, combat) consistent.

Product and startup opportunities

Hybrid fantasy worlds create new vendor niches:

- Asset marketplaces specializing in matched organic+mechanical packs (stone ruins with embedded circuitry).

- Middlewares for emergent-construction gameplay (attachment systems, durability, shared physics layers).

- SaaS tooling for procedural ruin generation tuned for level designers, producing maps with scaffolding for puzzles that contain tech artifacts.

A small team that ships a plug-and-play ‘relic and ruin’ kit for engines like Unity or Unreal can save other developers weeks of R&D—particularly for games that want the Zelda-inspired flavor without cloning gameplay.

Limits of the approach

- Narrative mismatch: if tech undermines stakes (e.g., too many ‘all-powerful’ devices), players lose investment.

- Scope creep: sandbox toys tend to balloon QA and balance costs.

- Tone drift: comedic or industrial-sounding tech can break immersion in a poetic fantasy setting.

Balancing restraint and surprise is the core craft move: add one big mechanical wonder per region or chapter rather than saturating the world.

Looking ahead: three practical implications

- Tooling for emergent experiences will become a product category. Expect more middleware that handles attachment rules, power systems and networked determinism so creators can focus on level design.

- User-generated machines and cloud sharing will push social features. Allowing players to publish contraptions or challenge maps extends playtime and monetization.

- AR/VR could be the best medium for ancient-tech discovery. Physical gestures paired with believable haptic or audio feedback will make puzzle-solving with relics feel more visceral.

For designers and founders, the takeaway is simple: the ‘lost technology in a mythic world’ motif is not merely aesthetic. It’s a design lever that unlocks mechanics, narrative economy and commercial opportunities if executed with discipline. Start with a single, memorable device. Let players invent use cases, then build the infrastructure that supports sharing and iteration—just like many modern Zelda entries have done.