A remarkably preserved mummified ice age kitten, the first known example of a saber-toothed cat mummy, has been unearthed in Siberia, sending ripples of excitement through the paleontological community. The exceptional state of preservation offers an unprecedented glimpse into the appearance and potential hunting style of these extinct predators. Details of the find were published Thursday in the journal *Scientific Reports*.

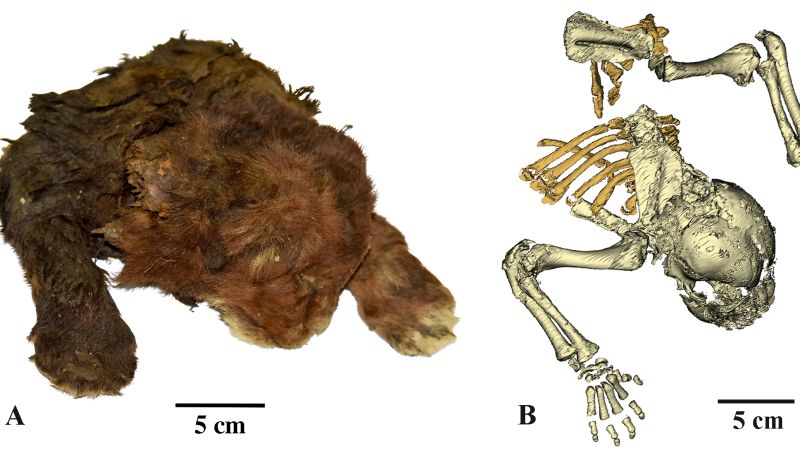

The partially mummified cub, boasting abundant fur and remarkably intact flesh covering its face, forelimbs, and torso, was discovered in permafrost near the Badyarikha River in northeastern Yakutia, Russia. Its short but exceptionally thick, dark brown fur measured between 20 and 30 millimetres in length. Alexey V. Lopatin, lead study author and chief researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciencesâ Borissiak Paleontological Institute, described the fur as surprisingly soft. "It's a fantastic feeling to see with your own eyes the life appearance of a long-extinct animal," Lopatin stated in an email to CNN. "Especially when it comes to such an interesting predator as the sabre-toothed cat."

The mummy represents the first evidence of the *Homotherium latidens

species in Asia, although fossilised bones have been previously discovered in the Netherlands and the Canadian Yukon. While other ice age mummies, such as woolly rhinos and mammoths, are known from the Yakutian region, mummified cats are exceptionally rare. Before this discovery, only two mummified cat cubs â both cave lions (*Panthera spelaea*) â had been found in the Uyandina River basin.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the cub is at least 35,000 years old, dating back to the late Pleistocene epoch. Its preservation is exceptional, with its forepaws retaining claws and the fleshy pads ("beans") characteristic of modern cats. Analysis of its incisor growth and comparison with lion cub anatomy indicate the cub was approximately three weeks old at the time of its death. Articulated pelvic and hind limb bones were also found frozen alongside the partial mummy.

However, significant differences exist between this saber-toothed cub and modern lion cubs of a comparable age. Its coat was darker, its ears smaller, and it possessed longer forelimbs, a larger mouth opening, and a more substantial neck. Notably, its upper lip was more than twice the height of a modern lion cub's, likely to accommodate its future long upper canines. The shape of its paw, more circular than a lion cub's and resembling that of a bear, suggests a potential reliance on powerful forearms for hunting, perhaps used to immobilise prey.

Paleontologist Jack Tseng, an expert in extinct mammal anatomy who was not involved in the study, expressed astonishment at the discovery. "I donât know if other paleontologistsâ minds are as blown as mine, but itâs like reality changes now that weâve seen this," he said. The finding provides a crucial opportunity to examine the anatomy of *Homotherium

beyond digital modelling based on fossil scans, offering a more complete understanding of its hunting techniques and evolutionary history within the broader feline family. The exceptionally well-preserved mummy is not only the first of its kind but also provides a unique lens through which to study the evolutionary trajectory of the cat family, tracing back almost to its origins. Further genetic analysis and skeletal examination are planned to unlock even more insights into this remarkable discovery.