Gobekli Tepe's Mysterious Carvings: Ancient Calendar or Comet Strike Record?

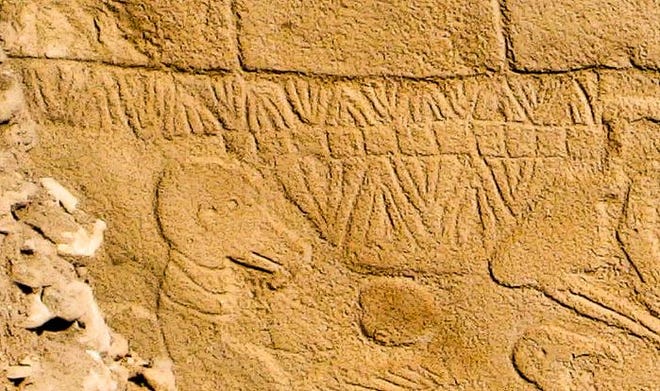

A study published in the journal Time and Mind suggests that carvings at the Gobekli Tepe archaeological site in Turkey, dating back nearly 12,000 years, could represent the world's oldest solar calendar. The site, already renowned as the oldest known place of worship, predates the Great Pyramid of Giza by a staggering seven millennia.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh have interpreted intricate carvings at Gobekli Tepe as a record of an astronomical event - potentially a devastating comet strike - that may have ushered in a momentous shift in human civilization. The team, led by chemical engineer Martin Sweatman, believes the V-shaped symbols etched onto pillars at the site represent individual days. By totalling these symbols on one pillar, they calculated a solar calendar of 365 days, comprised of 12 lunar months plus 11 extra days.

Further evidence suggests that a separate symbol depicting a V worn around the neck of a bird-like creature might represent the summer solstice. The researchers hypothesize that similar markings on other statues depict deities. This combination of solar and lunar cycles led them to conclude that the carvings could represent the earliest known "lunisolar calendar," predating other such calendars by millennia.

The researchers speculate that the calendar's creation was a way for ancient people to memorialize a cataclysmic event: a swarm of comet fragments that struck Earth nearly 13,000 years ago. They point to a pillar at the site depicting the Taurid meteor stream, believed to be the source of these fragments.

The study suggests that this comet strike around 10,850 BC could have triggered a mini-ice age lasting over 1,200 years, causing the extinction of numerous large animal species. This devastating event, the researchers argue, may have spurred the development of agriculture in the fertile crescent region of West Asia, as hunter-gatherers sought more reliable food sources. They believe the monument's continued importance for millennia suggests that the comet strike may have prompted the emergence of a new religion.

"This event might have triggered civilization by initiating a new religion and by motivating developments in agriculture to cope with the cold climate," said Sweatman. He also noted that the findings support the theory that Earth experiences increased comet strikes as its orbit crosses the path of circling comet fragments, normally experienced as meteor streams.

The discovery also implies that ancient people were capable of recording dates by observing the Earth's precession, a phenomenon in which the Earth's axial rotation alters the movement of constellations across the sky. This suggests that these early civilizations possessed accurate methods for tracking time, thousands of years before similar observations were documented in ancient Greece in 150 BC.

"Possibly, their attempts to record what they saw are the first steps towards the development of writing millennia later," Sweatman concluded.

The study's findings offer a compelling glimpse into the lives and beliefs of our earliest ancestors, suggesting a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos and the ability to record celestial events long before the advent of modern scientific tools. The potential link between the carvings and a catastrophic comet strike raises intriguing questions about the impact of astronomical events on the development of human civilization.