'A King Will Die': 4,000-Year-Old Lunar Eclipse Omens Deciphered

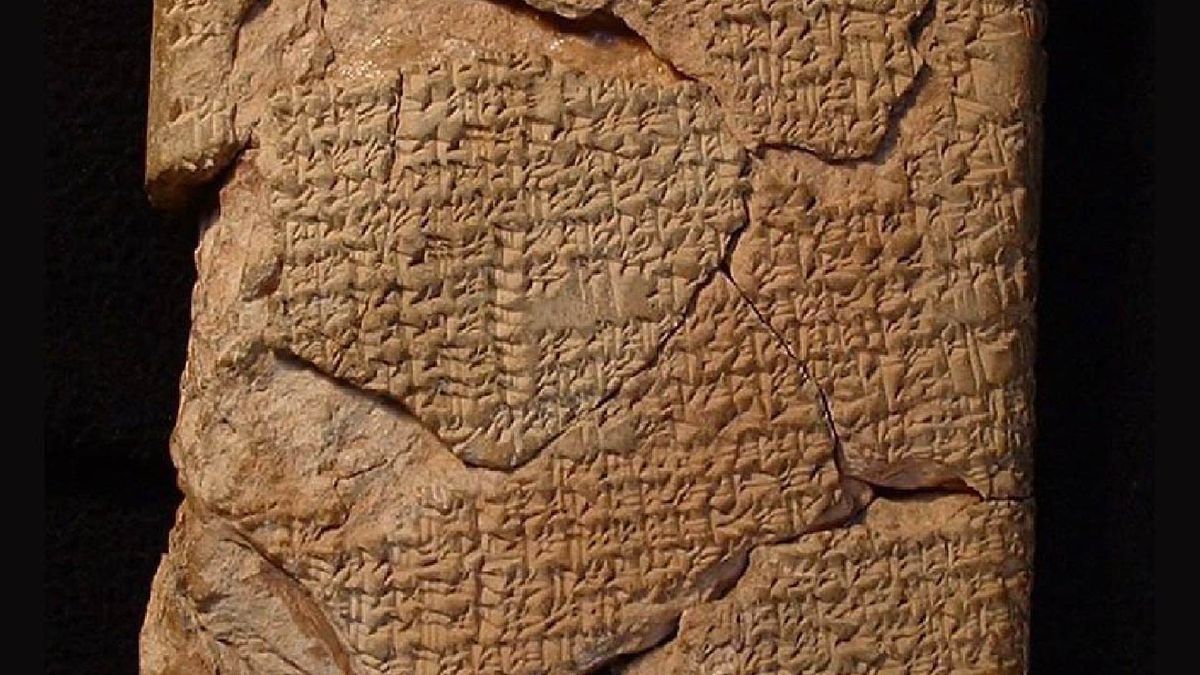

Scholars have finally unlocked the secrets of 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablets, discovered over a century ago in modern-day Iraq. These ancient clay tablets reveal a fascinating glimpse into Babylonian beliefs about lunar eclipses as harbingers of death, destruction, and pestilence.

The four tablets, described as "the oldest examples of compendia of lunar-eclipse omens yet discovered", were meticulously examined by Emeritus Professor of Babylonian at the University of London, Andrew George, and independent researcher Junko Taniguchi. Their findings, published in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies, shed light on the complex system of omens used by ancient Babylonian astrologers.

The authors of the tablets used a range of factors to interpret the celestial events, including the time of night, movement of shadows, and the date and duration of eclipses. Each eclipse held its own specific meaning, offering glimpses into the future.

One notable omen states that if an eclipse "becomes obscured from its center all at once [and] clear all at once", it signifies the death of a king and destruction for Elam, a region centred in present-day Iran. Another omen suggests that if the eclipse begins in the south and then clears, it foreshadows the downfall of Subartu and Akkad, both Mesopotamian regions of the time. A particularly ominous omen warns that an eclipse occurring in the evening watch signifies pestilence.

It is believed that Babylonian astrologers may have drawn upon past experiences to establish the meaning behind each eclipse omen. Professor George suggests that while some omens might have been rooted in real-world observations, followed by subsequent calamities, many were likely derived from a theoretical system that linked specific eclipse characteristics to specific outcomes.

The tablets, thought to have originated in Sippar, a thriving city in present-day Iraq, were likely created during the flourishing period of the Babylonian Empire. They found their way into the British Museum's collection between 1892 and 1914, but their contents remained untranslated and unpublished until now.

In Babylonia and other parts of Mesopotamia, celestial events held immense significance in predicting the future. The ancient people believed that these events were "coded signs placed there by the gods as warnings about the future prospects of those on earth", according to Professor George and Ms. Taniguchi. Those entrusted with advising the king would carefully observe the night sky and cross-reference their observations with established astronomical omens.

However, kings in ancient Mesopotamia did not solely rely on eclipse omens. If a particular omen predicted a threatening outcome, such as the death of a king, further divination through extispicy, the practice of inspecting animal entrails, would be conducted to confirm the validity of the omen.

If the entrails suggested danger, it was believed that certain rituals could be performed to annul the bad omen, thereby counteracting the forces of evil perceived to be behind it. This highlights a belief system where, even amidst ominous predictions, there was still hope for altering the course of the future.